Canada's Military Space Policy:

Part 2, The Changing Political Landscape

The recent announcement that the Department of National Defence (DND) is set to release an "updated" but not substantially changed Canadian military space policy over the next few months suggests a series of obvious questions.

In part one of this blog post, titled "The Axworthy Doctrine," I attempted to answer some of those questions by showing how the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990's led Canada to re-orient defense spending away from traditional Canadian priorities and towards international peacekeeping missions as defined by the concept of "human security."

This doctrine, initially viewed by the governing liberal party under Jean Chrétien as a great way to save money, also created a requirement to support a far more combat capable force on lengthy international missions.

The easiest way to do that, at least according to the Summer 2000 Canadian Military Journal article "Is the Sky Falling? Canada's Defence Space Program at the Crossroads," was to develop an indigenous military space communications and surveillance capability. According to the article:

But by 1994, this historic neglect of the Canadian military was no longer a reasonable option. According to the article:

But almost immediately, the Canadian military's precarious financial position virtually guaranteed the continued, heavy reliance on foreign, mostly US space assistance to fulfill defense needs which put a considerable strain on that relationship.

As well, an evolving US strategy (ironically enough, based on core concepts quite similar to those found in the Canadian advocated Axworthy Doctrine) slowly caused the Chrétien government to back away from some of the more critical practices associated with the US "war on terror."

So we've moved away from the situation existing throughout the 1960's to the 1990's where Canadian space policy provided no support whatsoever for military projects to the point where where the federal government perceives a need to develop an indigenous military space communications and surveillance capability to support Canadian troops on international missions and knew that they couldn't just rely on the Americans to do the job for them.

This brings us to the period around 2008 and the Harper Governments Canada First - Defense Strategy. How does the issuance of that government policy paper influence and effect the current and potential next Canadian military space policy document?

That will be the subject of our 3rd post on this topic.

Part 2, The Changing Political Landscape

The recent announcement that the Department of National Defence (DND) is set to release an "updated" but not substantially changed Canadian military space policy over the next few months suggests a series of obvious questions.

|

| Jean Cretien, the 20th Prime Minister of Canada. |

In part one of this blog post, titled "The Axworthy Doctrine," I attempted to answer some of those questions by showing how the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990's led Canada to re-orient defense spending away from traditional Canadian priorities and towards international peacekeeping missions as defined by the concept of "human security."

This doctrine, initially viewed by the governing liberal party under Jean Chrétien as a great way to save money, also created a requirement to support a far more combat capable force on lengthy international missions.

The easiest way to do that, at least according to the Summer 2000 Canadian Military Journal article "Is the Sky Falling? Canada's Defence Space Program at the Crossroads," was to develop an indigenous military space communications and surveillance capability. According to the article:

The massive troop deployments of the 1990s highlighted the immediate requirement for adequate indigenous Military Satellite Communications (MILSATCOM). The increased employment of precision guided munitions demonstrated a growing dependence on accurate strategic intelligence, satellite imagery, and satellite navigation and positioning. Also, the general increase in littoral operations by naval forces placed a greater dependence on accurate meteorological and geodetic capabilities.Why was the Liberal government reluctant to accept the "militarization of space" as a long existing fact? According to the article there was ample precedent for this reluctance:

As the (Canadian) government continued to commit Canadian Forces across the world, more and more space support was necessary. Reluctantly perhaps, the Liberal government accepted that the militarization of space was a long-existing fact that had to be publicly supported if it was to meet other foreign policy goals.

In essence, the longtime Canadian government policy, starting from the 1960's and continuing at least until the middle 1990's, was to simply "withdraw financial support" from the military in favor of civilian programs (like Telesat Canada, a federal government crown corporation formed in 1969 to improve communications in the far North) and scientific satellites.Canada’s endorsement of the United Nation’s treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in 1963 (the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty) and the United Nation’s Outer Space Treaty (UNOST) in 1967 were interpreted almost verbatim by Ottawa, and led to the removal of DRB (the Defence Research Board) control from most of Canada’s space projects.

Pierre Trudeau, the 15th Prime Minister of Canada in 1971.

The first Trudeau government saw no distinction between the militarization of space (placing military space assets in orbit) and the ‘weaponization’ of space (placing weapons in orbit), and moved quickly to deprive Canada’s military of any space assets or capability.

In 1968, the government withdrew financial support from most defence space projects, preferring instead to concentrate its resources on the development of a domestic satellite communications system.

But by 1994, this historic neglect of the Canadian military was no longer a reasonable option. According to the article:

As future space technologies all but eliminate Canada’s traditional geographic situational importance, Ottawa will have to rely on providing a share of the security burden rather than relying on the outdated American involuntary guarantee of protection.These new technologies, and the potential for even more radical improvements on the horizon helped the Canadian military to push forward a plan to insure that a requirement for a Canadian communications and surveillance capability would be at the core of the 1998 military space policy.

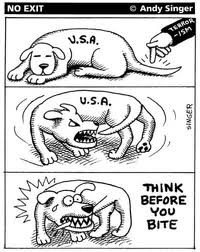

But almost immediately, the Canadian military's precarious financial position virtually guaranteed the continued, heavy reliance on foreign, mostly US space assistance to fulfill defense needs which put a considerable strain on that relationship.

As well, an evolving US strategy (ironically enough, based on core concepts quite similar to those found in the Canadian advocated Axworthy Doctrine) slowly caused the Chrétien government to back away from some of the more critical practices associated with the US "war on terror."

So we've moved away from the situation existing throughout the 1960's to the 1990's where Canadian space policy provided no support whatsoever for military projects to the point where where the federal government perceives a need to develop an indigenous military space communications and surveillance capability to support Canadian troops on international missions and knew that they couldn't just rely on the Americans to do the job for them.

This brings us to the period around 2008 and the Harper Governments Canada First - Defense Strategy. How does the issuance of that government policy paper influence and effect the current and potential next Canadian military space policy document?

That will be the subject of our 3rd post on this topic.